The Once and Future King: VC as an Asset Class in 2022 and Beyond

Reflections on our sector in a volatile year

This originally appeared on the 8VC blog.

In 2022, the technology sector experienced its biggest downturn in a generation, marking the end of a formidable bull run in Silicon Valley. Many are wondering what the downturn in tech equities means for venture capital as an asset class. Is VC better today than it was a few years ago? How does it compare to competing assets like the rest of private equity, public markets, cash, credit, etc?

As a part of the public launch of Opto Investments this week, a company we founded as ‘LIT’ and of which I am Chairman, I want to answer these questions at some length. Opto is a technology platform that will open up private markets to global investors like never before, which will be especially important in VC, as this asset class is notoriously difficult to access without the relevant network and experience. You can read more elsewhere about how the Opto platform works, but the underlying question remains: why should investment managers care about VC and technology markets in the first place, especially during a wipeout period like the present?

As an active entrepreneur for the last twenty years in Silicon Valley and beyond, and as a major venture investor for the last ten, I have strong opinions about this; at 8VC, we are constantly studying the global macro environment to assess where we are. What follows is my assessment of where things stand, and the case for why VC remains a top asset class and an important engine for progress.

Let’s get into it.

Venture capital is money put into innovative businesses — remember, venture comes from adventure — with the potential for high growth. In return for the cash investment, VC investors take equity stakes in those businesses. We build long partnerships with entrepreneurs to build and grow the businesses, leveraging our own expertise and networks to create value in the process. We deliver capital back to our investors when the businesses we’ve backed “exit” — usually this means being acquired or entering public markets.

The business of venture capital can be broken out into a few stages: finding, pricing, and winning investment deals; building companies; and exiting companies. Underlying all of these processes are an understanding of elite technology cultures, connections with the right people, and knowledge in the relevant industries.

Like other assets, the immediate future for VC returns could be choppy, with fewer exits and at lower prices. But in general, there are very good reasons to remain bullish on VC, both relative to historical performance, and relative to other places investors could put their money. Especially at the early stage, technology investment through top VCs remains one of the highest-returning investments.

The 2021 Exit Bonanza

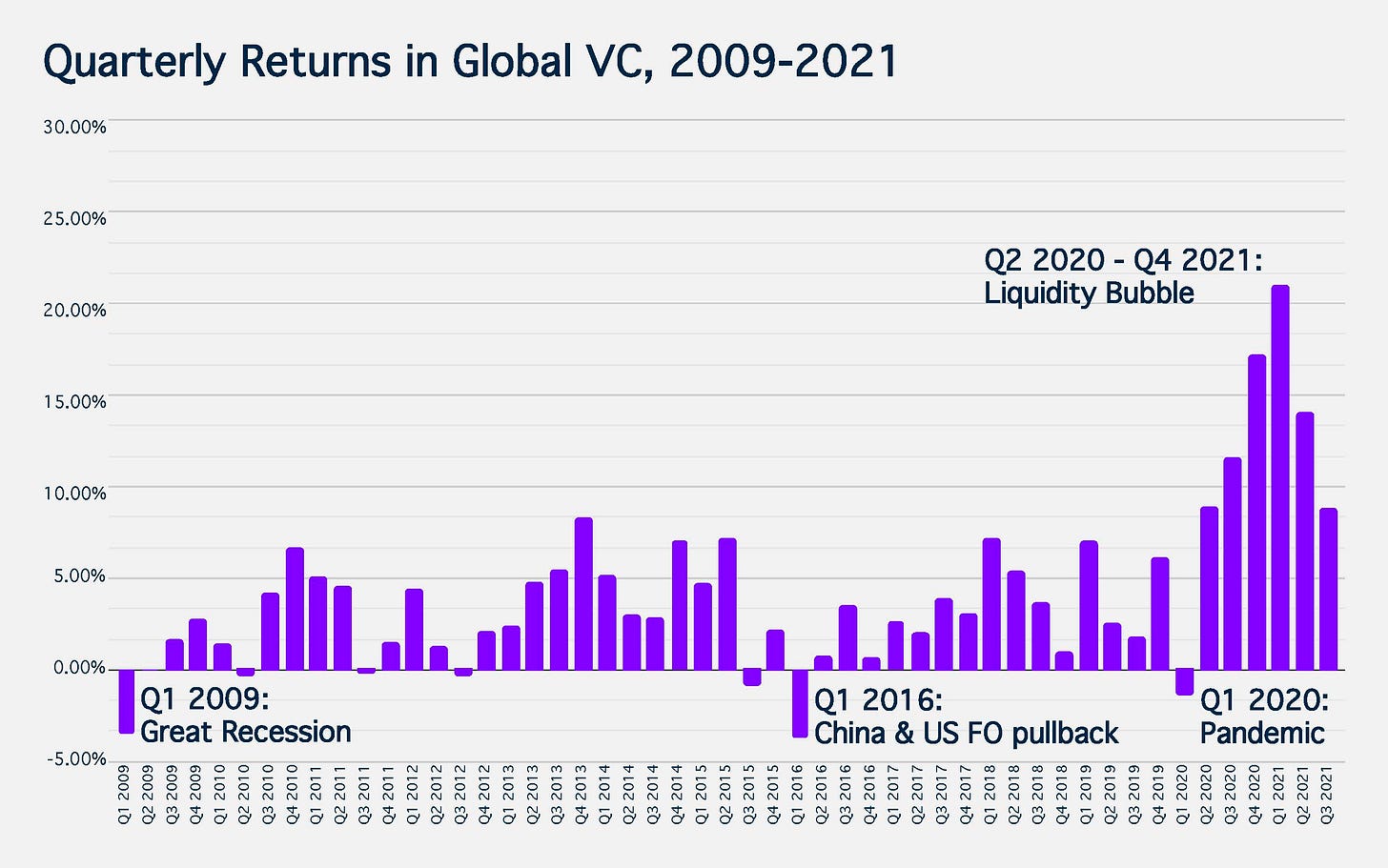

Late 2020 and 2021 saw the highest quarterly returns for VC since the height of the dot-com bubble. Liquidity and valuations exploded, driven by a sharp increase in the pace and scale of technology exits.

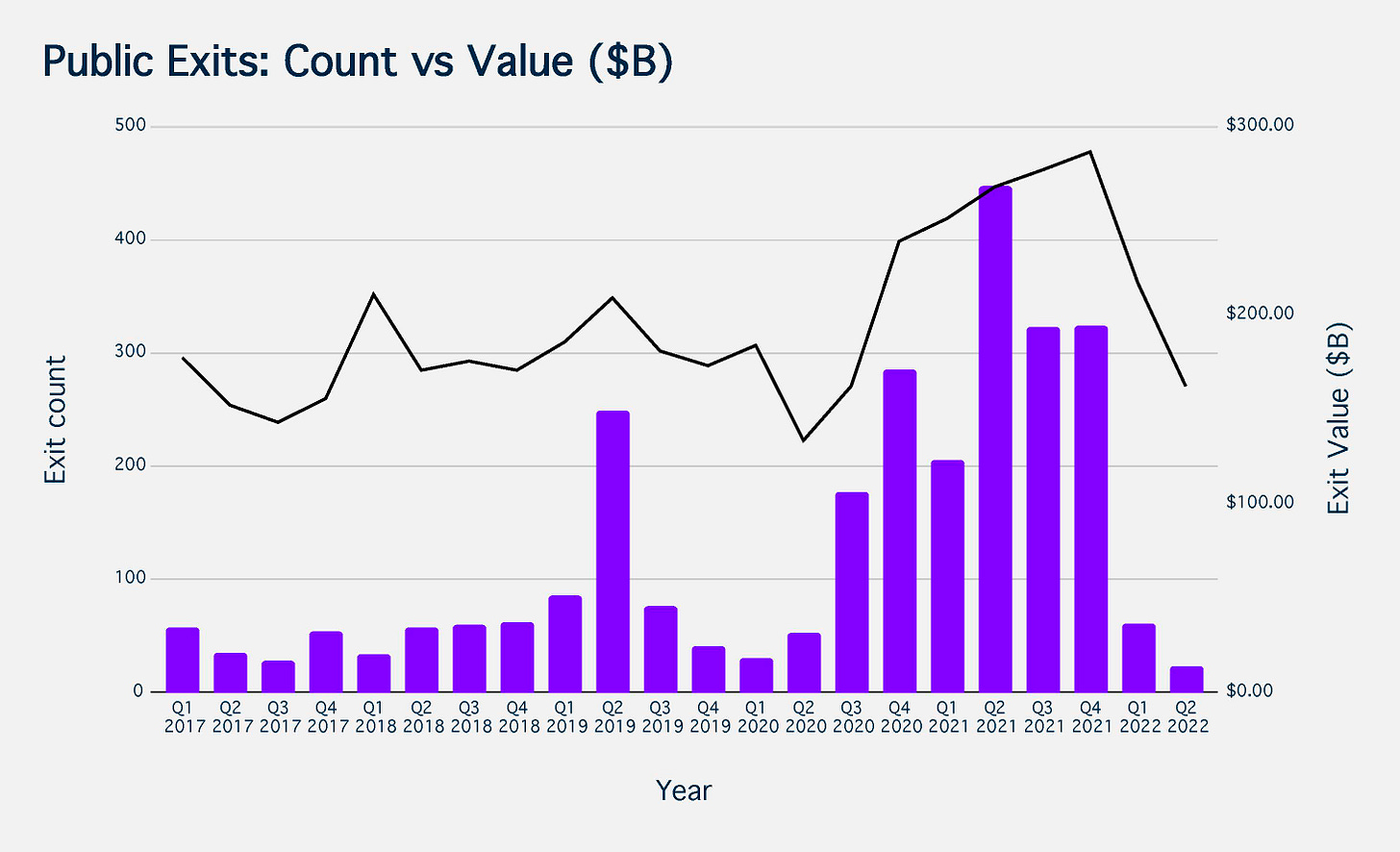

Liquidity from IPOs in 2021 was more than triple the number from 2020 and 2019, which were both record years in their own right. The data below show just how crazy the public markets went for technology in 2021, driving major returns for VC.

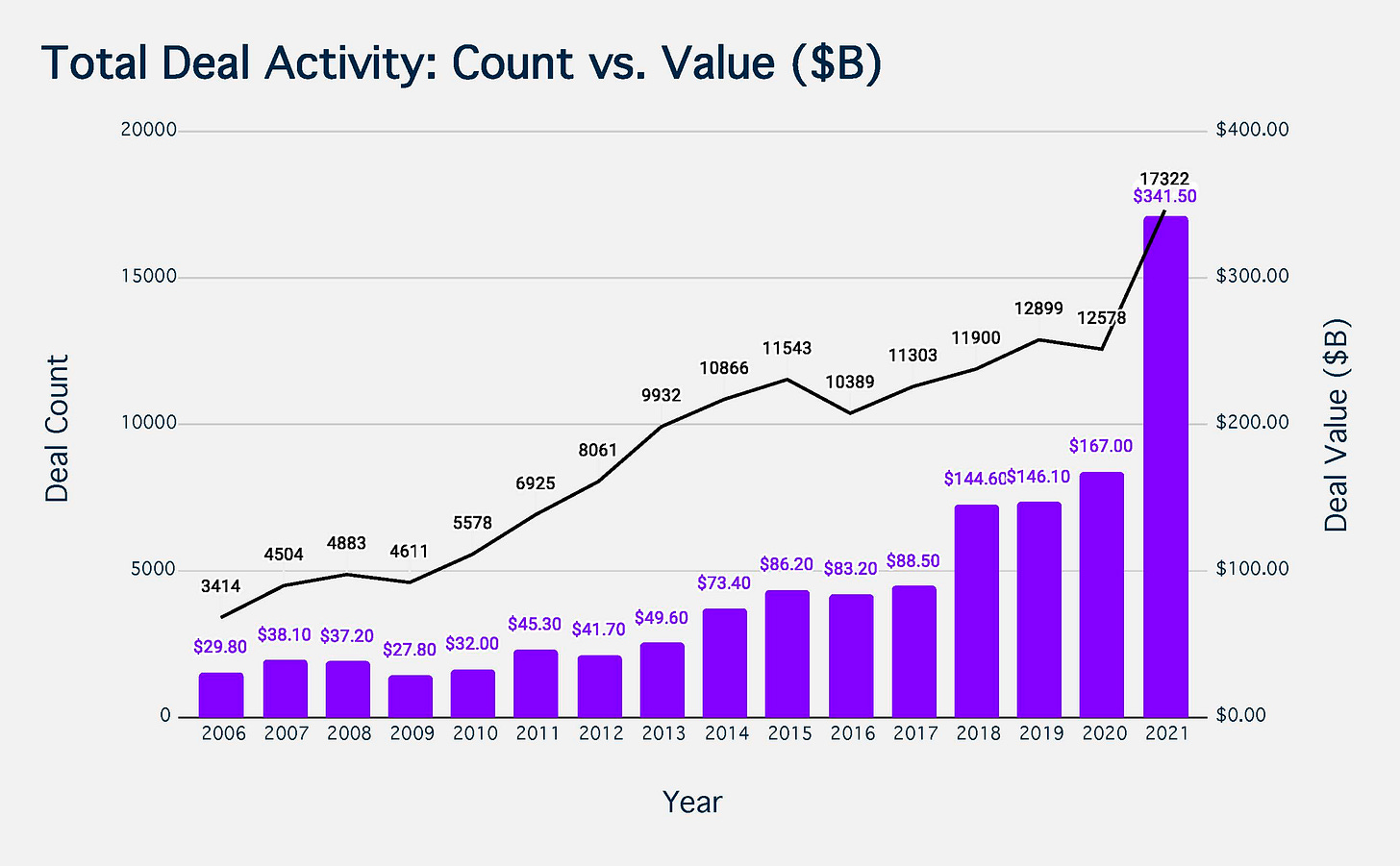

In 2021, dollars outpaced deals. While the total number of deals was up significantly (about 50% annually), it was the dollar-value of those deals that really surged (over 100%).

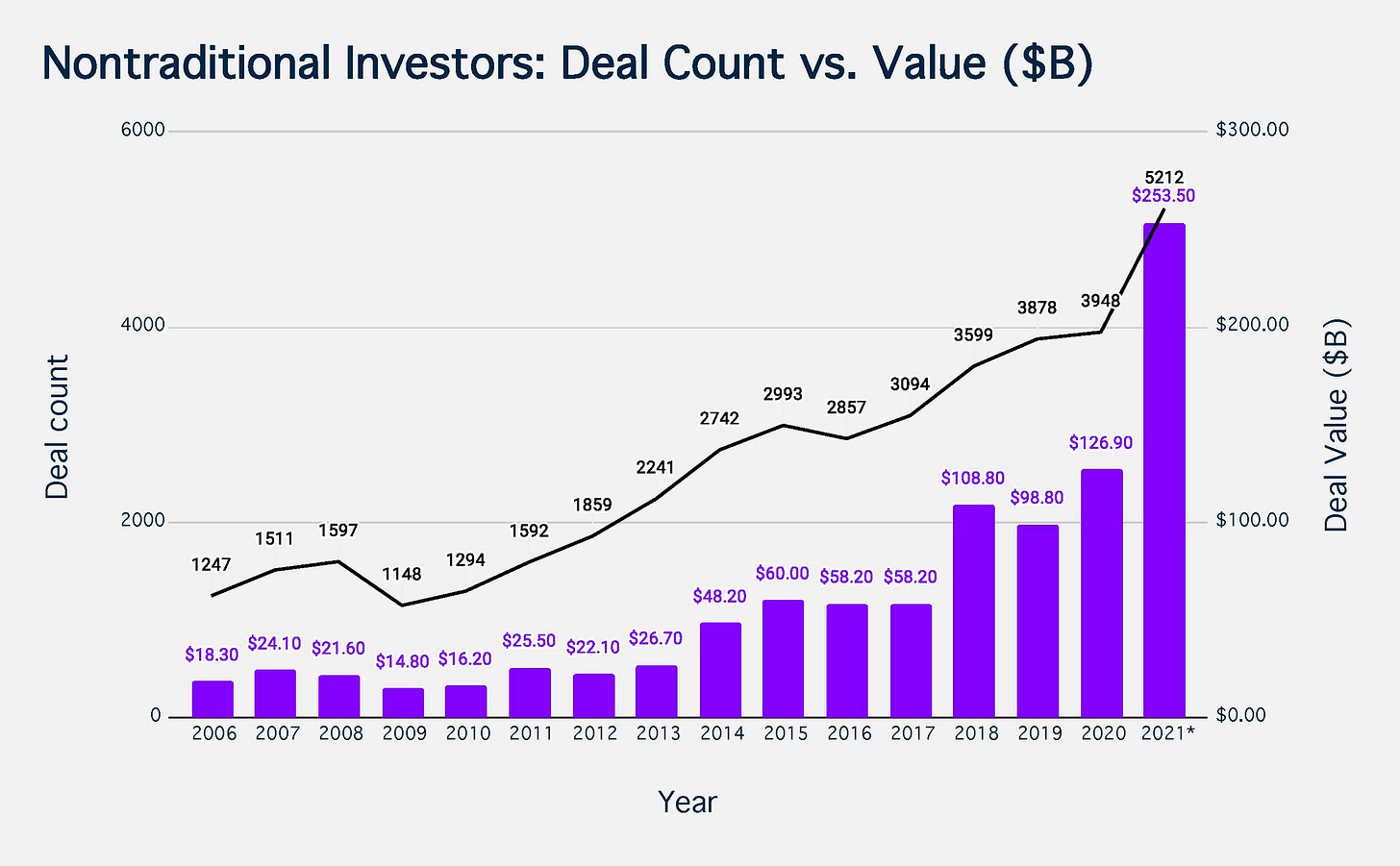

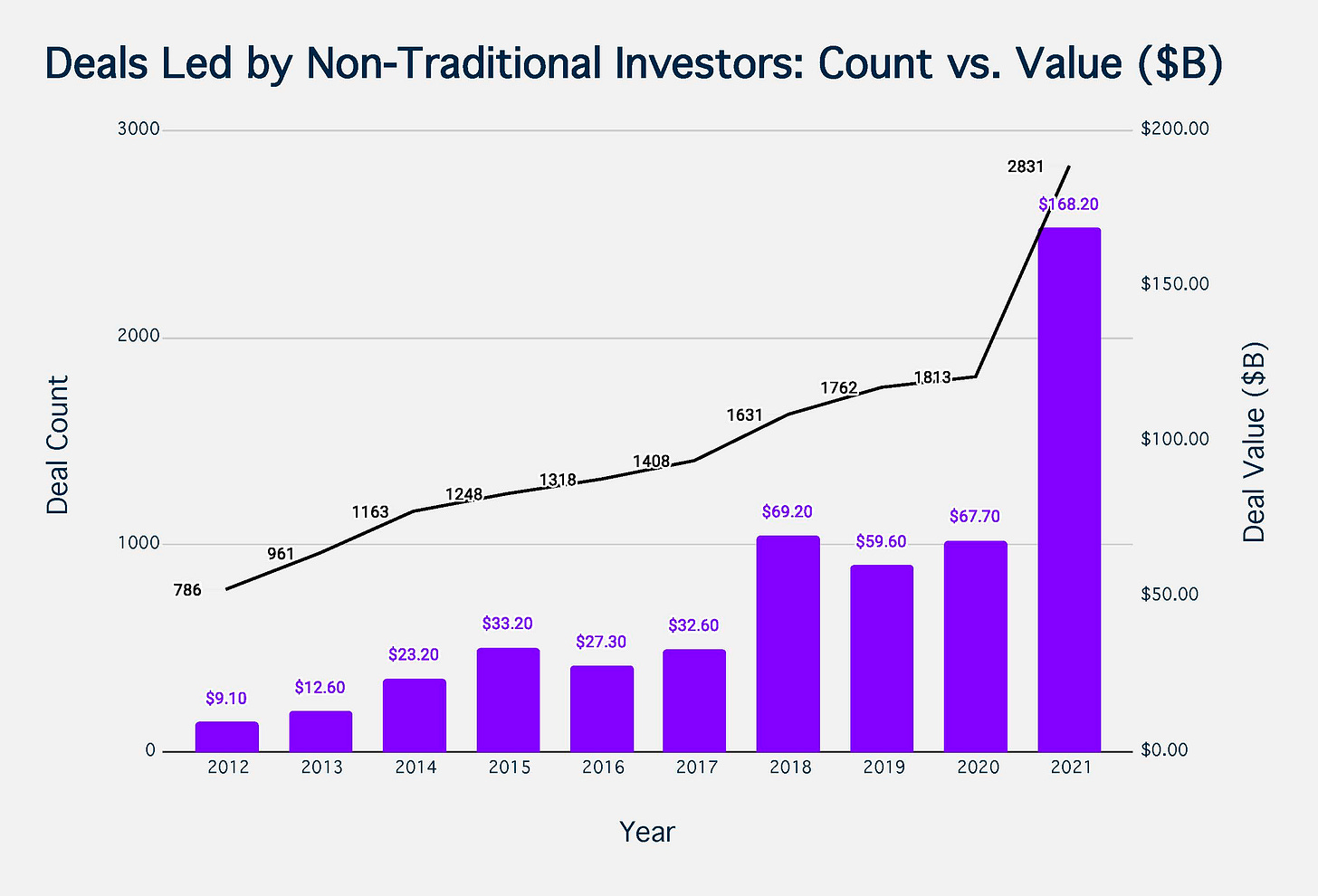

2020-2021 also continued the trend of non-VC investors - some insiders derogatively call them "tourists" - dominating the total investment in technology businesses, with over 60% of volume. In dollars, NTI participation surged over 100% year-over-year.

In deals led by non-VC investors, the total value nearly tripled from 2020-2021.

What happened? Essentially, it was euphoria. In the 2021 environment, technology investing had worked well for years and many argued that the valuation for exciting but hard-to-value businesses ought to be higher, reflecting two decades of investment success. Accordingly, investors propelled by lots of liquidity rode this market trend. With a few notable exceptions, the businesses that got funded — especially in the growth stage — were showing serious growth, high margins, and the potential to grow for years into eventually generating large cash flows. But their valuations were still extremely high compared to how markets historically value businesses, even in software.

By way of example: Peloton — a business with a great product that I use — peaked at a market cap of $60 billion, nearly 60 times the company’s year-forward gross profit. Teledoc — again, a great product that enables remote access to healthcare — went to $50 billion in early 2021, about a quarter the size of UnitedHealthcare at the time. Even Palantir — which I co-founded nearly two decades ago and believe in as strongly as ever — caught fire in the Reddit forums and climbed to an enterprise value of nearly $80 billion, 53 times the revenues it would ultimately earn in 2021. These are all good businesses, but they were priced so far ahead themselves that investor disappointment was inevitable.

Investors that went big on tech during the pandemic got to print great numbers on the way up, and many realized high returns from exits. In the late stage private markets, where exits didn’t take place, there could be more future pain as these assets correct in line with public equities.

As a result, funds focused on growth and late-stage could face serious headwinds for the next few years. There’s an adverse selection problem where many of the best companies simply won’t be raising. Businesses marked generously might be unwilling to raise as they try and grow into those valuations, so it will be tough to put money to work. Even if companies do successfully grow into their valuations, they will have spent years clawing their way back up, depressing IRRs for 2021 growth funds.

But even with pullbacks, the flood of money that venture funds raised through 2021 will enable good businesses to find the capital they need to grow and innovate — unlike 2002 when capital disappeared almost entirely. For 2021 vintage funds this will be scant consolation: since entry valuations in 2021 hit historic highs, those vintages still might not be the strongest. But on the flip side, current early-stage valuations are back to more sensible levels from 3-5 years ago, and these early-stage startups have a few years for markets to recover before they really need to access capital, whether in large growth rounds or in exits. These early investments have serious potential upside: leading 2022 vintage funds who know how to work with top talent and help create innovative companies should continue to perform well as usual.

2022 isn’t 2002

After 2000, there was a real question in global markets as to whether the Internet would work — and whether it was wrong for businesses to have committed capital to digital transformation. The Nobel Prize-winning economist Paul Krugman infamously declared, “By 2005 or so, it will become clear that the Internet's impact on the economy has been no greater than the fax machine's.”

When the dot-com bubble popped, many businesses and funds went down with it. Even the success stories of the era were starved of money and had to fight through a dark age in the 2000s — Amazon stock declined 90% and there was talk of bankruptcy. There is a fear of this happening again, especially among the dot-com veterans who built 1990s businesses that got wrecked. Thankfully, fears of another 2002 are unwarranted — technology won, and there is no doubt whether great technology matters to the world economy. In fact, it’s integral to every major business on earth, and most of the minor businesses too.

Public markets recognize this reality: the largest names in the S&P 500 are technology businesses.

Anybody who has spent time with top venture funds and made a serious effort to understand the latest in technology knows that demand for innovation remains high. If anything, the chaotic events of the past few years have elevateddemand for technology to address unexpected challenges, especially in critical, physical industries. There are hundreds of extraordinary new companies being built to address this demand right now.

The immediate historical analogy for our current inflation is the 1970s, where technology performed poorly. That’s because the underlying macro drivers of performance in the 1970s were pricing power and stable cash flows: tech, which then meant semiconductors, had famously cyclical cash flows and low pricing power, so of course it underperformed.

Tech now means consumer platforms and SaaS. In an inflationary environment, SaaS has real pricing power: software products literally save employee time, so their value strengthens as wage inflation rises. If SaaS had been around in the 70s, tech would have outperformed.

And that brings us back to the core question for VC: is it easier or harder for them to make great deals? Historical trends suggest it’s easier.

What to do in a Bear Market

In the 10-year crescendo leading up to 2020-2021, a favorable macro environment allowed mediocre investors without unique insight to profit from jumping on the tech bandwagon. When that bandwagon crashed as it did in late 2021, panic ensued and many fled. But for expert investors who can cut through the hype to identify talent and assess the economic impact of a given technology, it’s a buyer’s market.

The value of hunting for deals in a downturn shows up in the data: in 2009-2011, down and flat rounds (investments at lower-than-expected valuations, when investors were finding great businesses at “the right price”), actually outperformed the up rounds (when investors joined with others on hot investments). In all other years — the bull years — the opposite was true.

Top investors prove their worth in a crisis. When valuations always go up, capital is a commodity and founders just pick the highest bidder. Now, the value of experienced, honorable investors — who guide their founders through bad times as well as good — is clear. In an environment where fear abounds, the best founders are looking for more than just money from their backers; they want expertise.

VC is a game of skill: there’s always been a wide gulf between top investors and the rest (this effect is even more pronounced at small-medium funds). For smart investors who can identify how value is created, find contrarian bargains, and support their founders wisely and honorably, everything’s on sale today: it’s a fantastic time to invest.

A Great Time to Build Businesses

In addition to driving up the basic cost of VC — the cost of equity — market euphoria also clogged up a few channels that matter to startups. Cleaning those out makes today a better time to build businesses.

Talent is more accessible. Today, due to a number of factors, partnering with top talent isn’t as expensive. Overfunded companies in the past decade that arbitrarily bid up the value of engineers are today laying them off, or slowing hiring. The equity incentives at those businesses are also coming down, which makes early-stage work more attractive to the best engineers.

Less money will be wasted on zero-sum spend. When venture dollars are in oversupply, advertising channels become filled with noise, and it’s very expensive to be heard and seen. Normal advertising levels create a healthier environment, where businesses and investors don’t have to burn through their capital in an ad market crowded with high-budget competitors.

High-end VC remains one of the best asset classes there is. It’s a long-term investment based on the most solid thesis of the 21st century: that given time, the most talented people in the world can build better processes, technologies, and cultures that transform the biggest industries and life as we know it.

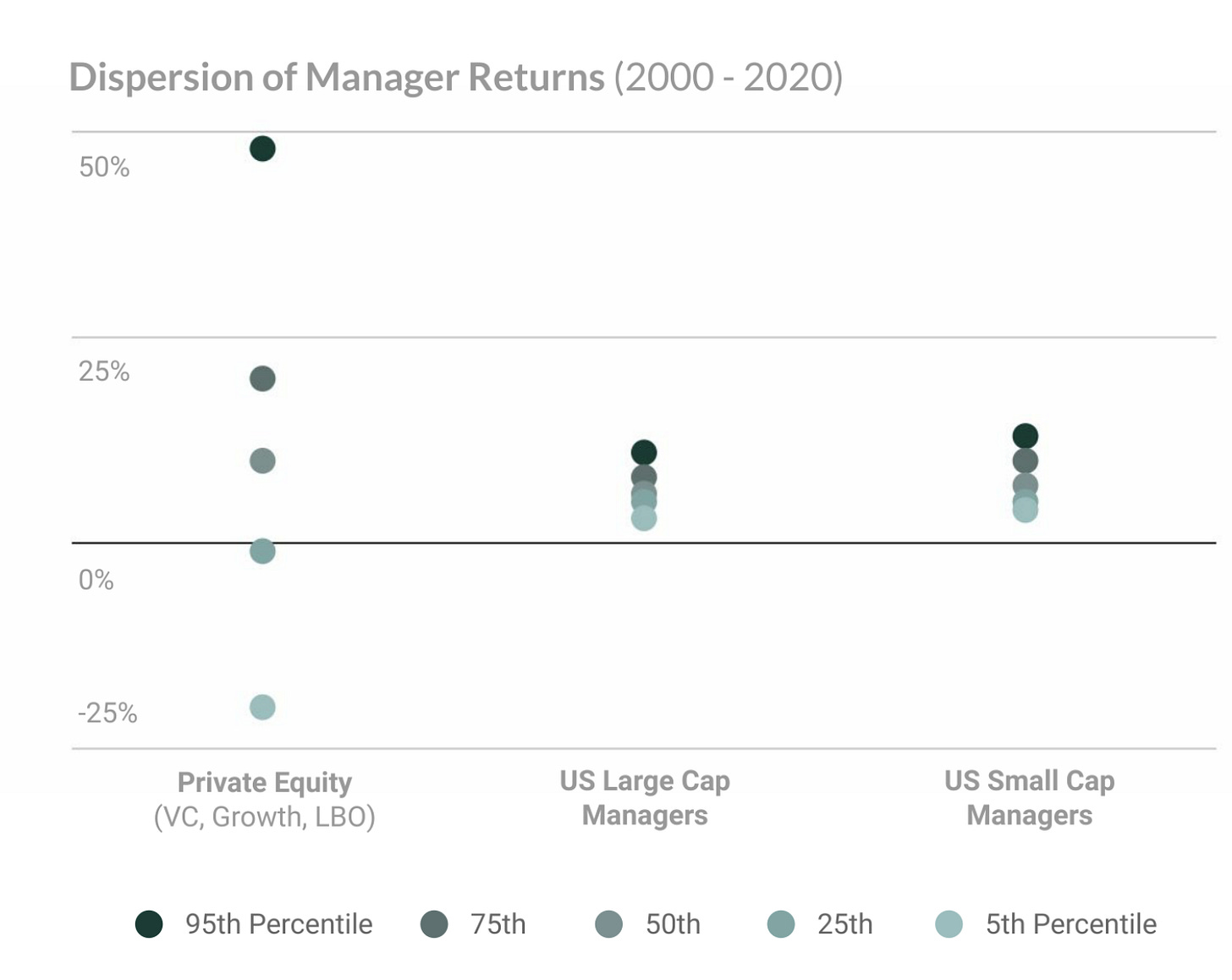

Especially at the early stage, and especially at top funds that are staying disciplined with the amount they raise and the size of the team they hire, VC is an important asset for large investors. Moreover, VC as an asset class has been unique in its level of autocorrelation (the correlation between fund returns of different vintages) and return dispersion (the difference in returns between a top and a median fund). Unlike many other asset classes, top funds tend to stay at the top — by a large margin.

If you believe that a given VC fund has (a) real expertise in technology and entrepreneurship, (b) the reputation and network to attract top founders, and (c) the proven skills and experience making great deals, then investing in them is a uniquely valuable proposition — making VC a top global asset class for the future.