Make the FDA Great Again!

We're long overdue for bold reforms to keep us ahead of China, and save more lives

Dear Readers,

My colleagues at 8VC and I published another policy piece, this one around biotech innovation and the FDA. This has my name on it, but it includes the work of multiple people, many with PhD's in relevant areas.

We're excited to partner with the new administration on some non-partisan issues here that are absolutely critical for our country.

It's not a short read - this is a complex area, and there's a lot to fix!

But everything ties back to some key principles, not least innovation and competition, inside and outside of government, and eliminating unnecessary rules: especially when they make things harder on US companies versus the competition.

Best,

Joe

For decades, the United States has led the world in biotech and pharmaceutical innovation. American firms dominate the global landscape, representing six of the top ten pharmaceutical and seven of the top ten medical device companies by market capitalization.

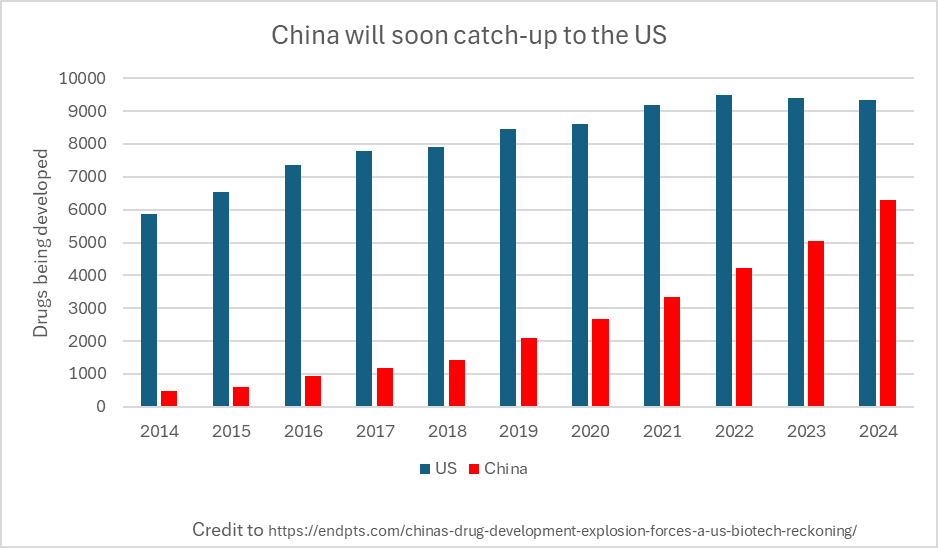

But dominance is now at risk: not from external sabotage, but from our own regulatory sclerosis. While we drown breakthrough science in red tape, China has a laser-like focus on speeding up scientific progress and the subsequent adoption of innovation. China has embraced CRISPR, leapfrogged the west in cell therapy, developed sophisticated animal models, and rapidly expanded its biotech exports from near-zero in 2016 to nearly 30% of new assets in the world today. Capital is following suit: hedge funds, venture dollars, and strategic acquisitions are pouring into Chinese biotech, responding to a regulatory environment that’s more permissive of experimentation and progress. This is not theoretical. It déjà vu: we have watched this story unfold before across semiconductors, telecommunications, energy, and manufacturing.

If we don’t course-correct, we will cede the biotech future to China and the Chinese Communist Party. That means not just offshoring high-skilled jobs, but becoming dependent on an adversary for critical medicines and biological manufacturing. In synthetic biology, anti-infectives, and medical supply chains, this dependency is already here. And yet, perversely, our rules make it harder each year rather than easier to build at home.

Competition is a good reminder and motivating force, but there are good reasons to support innovation in the US regardless of what China does or doesn’t do.

For the American people, besides better population health and longer lives, novel medicines that eventually go generic are the most deflationary part of the medical system. Overall healthcare costs to treat the same diseases to the same outcomes are dramatically lower if there are great medicines – an important priority given our $2T budget deficit.

As entrepreneurs and investors in drug manufacturing, drug discovery and development and clinical trials optimization, we have a front row seat to problems and opportunities in biotech.

What follows here is our prescription for the FDA (and in some cases HHS) — to accelerate and reduce the cost of new therapies, encourage more US-based research & bio-manufacturing, and stop the government from accidentally destroying our fraying lead in this critical sector.

-- Joe and the 8VC Bio Team

1: Curb burdensome regulations to accelerate clinical development

The speed of a clinical trial must become a first-class priority. Every day wasted due to regulatory sclerosis is a day a patient loses forever. Accelerating trials isn’t just smart—it’s essential if America wants to stay ahead globally, cut costs, and rapidly separate breakthrough therapies from failures and transparently share the findings with the public. Faster trials reward bold innovators and, most importantly, save lives. To keep innovation at home, we need to both learn from competitors and seek new reforms of our own that make development move faster while preserving our values as a society.

Thematically, the FDA must recognize speed as one goal of clinical research alongside other priorities. In light of its value, sometimes speed should win out against other factors and the FDA (through each of its centers: CBER, CDER, CDRH and CVM) should include in its guidance a cost-benefit analysis that includes the time costs of a clinical trial with all the attendant patient harm that occurs when a patient is deprived of a novel medicine by waiting for a trial outcome.

We are encouraged by FDA Commissioner Marty Makary’s commitments to reducing overly-long drug approval processes. A few specific ideas that would strike a better balance follow.

1.A. MAKE GMP STANDARDS MORE SENSIBLE TO ACCELERATE CLINICAL TRIAL STARTS.

In the U.S., anyone running a clinical trial must manufacture their product under full Good Manufacturing Practices (GMP) regardless of stage. This adds enormous cost (often $10M+) and more importantly, as much as a year’s delay to early-stage research. Beyond the cost and time, these requirements are outright irrational: for example, the FDA often requires three months of stability testing for a drug patients will receive after two weeks. Why do we care if it’s stable after we’ve already administered it? Or take AAV manufacturing—the FDA requires both a potency assay and an infectivity assay, even though potency necessarily reflects infectivity.

This change would not be unprecedented either. By contrast, countries like Australia and China permit Phase 1 trials with non-GMP drug with no evidence of increased patient harm.

The FDA carved out a limited exemption to this requirement in 2008, but its hands are tied by statute from taking further steps. Congress must act to fully exempt Phase 1 trials from statutory GMP. GMP has its place in commercial-scale production. But patients with six months to live shouldn’t be denied access to a potentially lifesaving therapy because it wasn’t made in a facility that meets commercial packaging standards.

1.B. EMBRACE PARTIAL HOLDS AND LIMIT FROZEN TRIALS.

Today, if a cell therapy trial has an open question about injection safety, it is common for the FDA to issue a clinical hold and grind the entire trial to a halt while that singular concern is addressed to satisfaction. But in a world of clearer thinking we would let recruitment, leukapheresis, and prep continue while sponsors addressed this point problem.

Stopping everything over one concern is not scientific rigor. When we consider the immense costs of type 2 error: it is laziness wrapped in paternalism. Rather than freeze the entire study over a single protocol concern, the agency should authorize partial progression as much as possible.

1.C. LET SCIENTISTS DESIGN ADAPTIVE TRIALS, CHALLENGE TRIALS AND TEST OTHER MODERN CLINICAL TRIAL APPROACHES.

Challenge trials had the potential to save lives during the COVID pandemic (e.g. tocilizumab or dexamethasone) but were blocked by institutional timidity. Both the FDA as well as site-level institutional review boards (IRBs) put up barriers to implementation – yet another example of sacrificing speed for safety while ignoring the associated costs.

From challenge trials to adaptive and seamless designs, there are a number of trial designs that are statistically sound and well-established, yet still treated as suspicious novelties. Every center – CBER, CDER, CDRH, and CVM – should be willing to consider well-designed studies that sacrifice some degree of caution where there is commensurate benefit with respect to speed.

IRBs are a separate can of worms. There are a number of ideas from standardizing review timelines and criteria to creating “by right” fast tracks to IRB approval that would all have a salubrious effect on the health of the American biomedical R&D enterprise.

1.D. SIMPLIFY REGULATIONS FOR CLINICAL TRIAL MONITORING.

During the pandemic, many clinical trials were forced to go remote and utilize modern digital tools to monitor patients. Nothing broke, and this experience showed how much can be done to modernize clinical trials to bring down their costs. For example, the PANORAMIC trial (conducted in the UK) successfully tested the effects of Molnupiravir on symptom resolution in an entirely digital trial with over 26,000 participants. Unfortunately, the FDA has regressed since — issuing guidance documents in 2024 that mandated a return to the pre-pandemic standard and withdrawing over 40 guidance documents that permitted fully remote trials during the pandemic. Fully or partially remote digital endpoints, previously allowed such as in pharmacokinetic measurements, were reverted to the pre-pandemic policy that emphasizes frequent in-person collection. Predictably companies dedicated to remote digital clinical trials, such as Science37, have failed as a result of the FDA’s changing guidance despite many remote trials working well during the pandemic.

The FDA should not impose such a strict requirement and thereby oppose remote and/or digital endpoints over traditional ones. Instead, it should acknowledge that remote trials are in-fact different from an in-person trial and should be held to different, but appropriate, regulatory standards (“risk-based monitoring”). If clinical trial sites refuse to modernize and hide behind bureaucracy and IRBs rather than change, the FDA should discourage sponsors from trial sites with ancient practices and favor data from the most up-to-date sites.

1.E. ACCELERATE REVIEW OF TRIAL RESULTS AND REDUCE MINDLESS PAPERWORK WITH AI.

Drug approval today is mired in paperwork and delay. After a multi-year Phase 3 trial, sponsors spend another six months compiling thousand-page clinical study reports, before waiting an additional year or more for FDA review. Much of this lag is arbitrary: FDA won’t review nonclinical or quality modules until the full package is submitted, and clinical reports can’t even be written until after trials conclude. The entire process is designed around human bottlenecks — manual data curation, reporting, and review — each step handled by cost-plus vendors who have no incentive to move faster.

This can and should be replaced by continuous, structured, real-time data submission. With modern AI and digital infrastructure, trials should be designed for machine-readable outputs that flow directly to FDA systems, allowing regulators to review data as it accumulates without breaking blinding. No more waiting nine months for report writing or twelve months for post-trial review. The FDA should create standard data formats (akin to GAAP in finance) and waive documentation requirements for data it already ingests. In parallel, the agency should partner with a top AI company to train an LLM on historical submissions, triaging reviewer workload so human attention is focused only where the model flags concern. The goal is simple: get to "yes" or "no" within weeks, not years.

1.F. PUBLISH RESULTS, EVEN IF DATA ISN’T FLATTERING.

Clinical trials for drugs that are negative are frequently left unpublished. This is a problem because it slows progress and wastes resources. When negative results aren’t published, companies duplicate failed efforts, investors misallocate capital, and scientists miss opportunities to refine hypotheses. Publishing all trial outcomes — positive or negative—creates a shared base of knowledge that makes drug development faster, cheaper, and more rational. Silence benefits no one except underperforming sponsors; transparency accelerates innovation.

The FDA already has the authority to do so under section 801 of the FDAAA, but failed to adopt a more expansive rule in the past when it created clinicaltrials.gov. Every trial on clincaltrials.gov should have a publication associated with it that is accessible to the public, to benefit from the sacrifices inherent in a patient participating in a clinical trial.

1.G. BACKLOAD COSTLY PRE-CLINICAL REQUIREMENTS.

The FDA routinely imposes preclinical testing requirements that delay clinical trial starts without improving patient safety. A common example: reproductive toxicity studies are often required before starting Phase 1 trials, despite the fact that virtually no early-stage trial allows pregnant participants, and most exclude anyone not using contraception. This kind of front-loading — demanding exhaustive data before any human is dosed — adds significant time and cost with minimal marginal value. The earlier the requirement, the higher the burden for startups and innovators, and the more capital is spent chasing paperwork rather than clinical insight.

The solution is to shift unnecessary preclinical burdens to later in the development process. Regulatory demands should be sequenced to align with real risk—what is happening, and when, in the trial—not imposed by bureaucratic tradition. Each FDA center should be instructed to optimize for speed to clinical data. That means approving trials with just enough data to begin safely, while deferring noncritical studies (like long-term toxicology or reproductive assays) to later phases.

2: Reform approval criteria to allow patients access to more medicines

As has been well documented elsewhere, today’s FDA is too concerned with denying access to drugs, devices and treatments in the name of patient safety at the expense of denying patients access to care they deserve. Untold numbers of people, in some estimates millions, might be alive today if the FDA had approved treatments faster or with a greater degree of risk appetite.

Alongside making trials go faster, an administration dedicated to expanding human lifespan ought to provide greater access to these sorts of life saving, or extending, treatments by tailoring rare disease approvals to disease prevalence, rethinking the core drug approval framework and increasing the number of groups that can say yes (rather than veto) an approval as well as getting everyone access to AI as fast as possible.

2.A. RIGHT-SIZE TRIALS FOR RARE DISEASES AND RENEW THE PRV PROGRAM.

Today there are thousands of ultra-rare diseases with less than 1000 patients in total, some as small as mere tens of patients. Yet despite these tiny populations, the FDA sometimes demands unreasonably large trials encompassing 100s of patients in order for a drug to garner an approval. This is obviously impractical and effectively denies these patients access to medical treatments. Today, ultra-rare diseases are left underfunded and underinvested due to these FDA shortcomings.

However, the Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER) can immediately fix this problem with clear and precise guidance. CBER should issue guidance that no trial for a rare disease will be less than 5 patients nor otherwise require more than 1% of the relevant indication, ensuring that there’s a rapid path to approval and commercial incentive to get these cures and treatments out to patients. For N of 1 disease, special allowances should also be made to avoid stifling cures. Under the Food Drug and Cosmetic Act (FDCA), CBER has wide latitude to determine the appropriate trial size and can act on this recommendation immediately.

Beyond clinical trial size, as has been written about by many others, the priority review voucher (PRV) program, which expired last year, has been invaluable towards incentivizing the development of rare drugs and its existence has directly led towards drug approvals and lives saved. Unfortunately the FDA cannot act alone here, Congress must re-authorize the PRV program immediately. As Congress does so it should consider expanding the PRV program to include other areas of unmet need where insufficient drug development is occurring, such as treatments for substance use disorders.

2.B. UPDATE THE GENERAL DRUG APPROVAL FRAMEWORK TO INCORPORATE PROGRESSIVE APPROVALS.

The basic concept of a Phase III clinical trial that requires thousands of patients across numerous facilities, and hundreds of millions of expense, dates to the mid-20th century. Yet it still forms the basis for the FDA deciding which patients are allowed to have the freedom to take the treatments they want and those that are denied their rights to choose which substances they put inside their bodies. Despite the tremendous advances in real-world data and real-time analytics that exist, the FDA hasn’t undertaken a wholesale re-thinking of our general drug approval frame.

During the initial AIDS crisis in the 1980s, scores of patients fought the FDA for the right to access experimental but life saving treatments; they were successful in winning an accelerated approval process. Still, these processes are limited, and have frequently required FDA leadership to “overturn” risk averse FDA staffers in spite of clear evidence that the FDA’s risk aversion is costing lives (see here). When the FDA does occasionally reduce regulatory requirements, it has been shown to clearly save lives. It is well within the authority of each FDA center (CBER, CDER and CDRH) to determine what constitutes “safe and effective” since there is no single bright line scientifically. There are always tradeoffs, no therapy is without risk and no therapy is guaranteed to work all of the time.

What would a first principles approach to drug approvals look like? It would ensure a few things:

Transparency as the default. Trials and reviews must produce statistical evidence that patients, doctors, and payors can independently assess—restoring trust in medicine through openness, not secrecy.

Approval as the default once safety is established. Especially for acute or life-threatening diseases, delays should require justification, not progress.

Robust post-approval monitoring. Faster approvals must be paired with real-time data collection and public reporting to catch issues early and continuously refine risk-benefit assessments.

Approvals should be progressive, allowing access at the earliest possible opportunity while maintaining a high standard of transparency for patients and physicians to make informed choices.

Would it work? Evidence suggests payers, providers and patients are quite capable of making independent judgments about the cost and benefit of drugs. One example: the FDA approved Aducanumab, an Alzheimer's drug. Despite FDA approval, payers and patients both rejected the drug; as the benefits shown in clinical trials were so small that nobody showed interest. On the flip side, patients and doctors are also able to judge when a drug is better than whatever a single FDA staffer has said; a perfect example of this is semaglutide (Ozempic). Approved in 2017 for diabetic patients, the world was able to see the profound benefits in obesity rapidly, and doctors facilitated access to millions of patients despite the FDA not approving semaglutide in weight loss for 4 years in 2021. The FDA sought a phase 3 trial rather than simply collecting post-approval data from the millions of patients taking it.

Thus the FDA should adopt a general approval frame as we lay out above, focused on providing the public with as much freedom and choice as possible, and enforcing transparent data collection requirements on innovators. CBER, CDER and CDRH could enact these regulatory changes today simply by issuing new guidance on what constitutes safe and effective therapies; they have wide latitude under legislation to do so.

2.C. DIVERSIFY DRUG APPROVAL PATHWAYS THROUGH COMPETITION.

The current system relies on a single gatekeeper: the FDA. Its centralized authority leaves no room for dissenting scientific views, regional priorities, or alternative models of risk tolerance. Patients are held hostage to the judgment of a single bureaucratic body—one increasingly captured by politics and outdated norms. Even implementing a progressive approval framework by default as described above (2.B.) will not solve this problem.

We need multiple competing approval frameworks within HHS and/or FDA. Agencies like the VA, Medicare, Medicaid, or the Indian Health Service should be empowered to greenlight therapies for their unique populations. Just as the DoD uses elite Special Operations teams to pioneer new capabilities, HHS should create high-agency “SWAT teams” that experiment with novel approval models, monitor outcomes in real time using consumer tech like wearables and remote diagnostics, and publish findings transparently. Let the best frameworks rise through internal competition—not by decree, but by results.

3: Fix drug manufacturing and medical resilience for the nation

Many Americans depend on crucial drugs, from anesthetics used in surgeries to tumor busting drugs to keep cancer at bay or insulin for diabetics. Yet as a country we have become ever more dependent on drug imports to ensure the health and well being of our country. So critical are these drug imports that they are one of the very few categories exempted from the most recent global tariffs despite the repeated subsidies and trade barriers other countries enact to maximize their own manufacturing (for example in China). The FDA, and HHS, must undertake significant steps to harden America’s drug supply against future disruptions, prepare the manufacturing and drug development system to better respond quickly to future crises and ultimately stop any American efforts that implicitly incentivize offshoring.

3.A. HARDEN AMERICA'S DRUG SUPPLY CHAIN FOR POTENTIAL DISASTERS AND CONFLICTS.

The COVID-19 pandemic exposed the vulnerabilities in the U.S. medical supply chain, with over 90% of generic sterile injectable drugs being manufactured abroad, primarily in countries like China and India. During the COVID crisis, export restrictions and supply chain disruptions led to critical shortages of essential medications. Even before the pandemic, this has been a problem, with declining shares of drugs being made in the US and EU compared to China and India. As we saw during the pandemic, such countries (especially China) may choose to hoard supplies they manufacture. In the event of a major crisis involving China, this represents a grave threat.

The FDA has system wide knowledge of the supply chains for critical drugs contained within its Drug, Biologics or Device Master Files (DMFs / BMFs / MAFs). The FDA (through each of the OPQ, OCBQ and OPEQ) should conduct a review of all DMFs to determine which drugs (APIs, formulations, fill-finish and packaging) are overly reliant on risky links in the supply chain. For those drugs, the respective center should mandate that manufacturers immediately establish new manufacturing sites in the US (or treaty allies) in order to maintain approval. Similar reviews and mandates to on-shore or ally-shore would also be prudent for medical devices, diagnostics and pre-clinical tools/assays that the FDA requires in its applications.

3.B. REBUILD THE ADMINISTRATION FOR STRATEGIC RESPONSE AND SUPPORT RAPID DOMESTIC MANUFACTURING AND CLINICAL TRIALS.

HHS spends billions-per-year on stockpiles of pharmaceuticals and medical supplies, preparedness and BARDA funding speculative research on potential future infectious disease threats. However these billions have failed to serve Americans in times of need; with a stockpile being full of expired drugs and supplies that are of no use, preparing supplies in reactionary ways that leave it unprepared for the next crisis, and being unable to quickly and efficiently deploy the capabilities that it does contain.

We support the reorganization of BARDA, ARPA-H, and ASPR into a more agile structure under the Administration for a Healthy America. But success depends on clear priorities. The new office should focus on three: (1) enabling rapid clinical trials to generate real-time evidence during crises, (2) building flexible domestic manufacturing capacity for drugs and devices, and (3) empowering state-level readiness efforts through the CDC.

Clinical trials like the RECOVERY trial and manufacturing efforts like Operation Warp Speed were what actually moved the needle during COVID. That’s what must be institutionalized. Similarly, we need to pay manufacturers to compete in rapidly scaling new facilities for drugs already in shortage today. This capacity can then be flexibly retooled during a crisis.

Right now, there's zero incentive to rapidly build new drug or device manufacturing plants because FDA reviews move far too slowly. Yet, when crisis strikes, America must pivot instantly—scaling production to hundreds of millions of doses or thousands of devices within weeks, not months or years. To build this capability at home, the Administration and FDA should launch competitive programs that reward manufacturers for rapidly scaling flexible factories—similar to the competitive, market-driven strategies pioneered in defense by the DIU. Speed, flexibility, and scale should be the benchmarks for success, not bureaucratic checklists. While the drugs selected for these competitive efforts shouldn’t be hypothetical—focus on medicines facing shortages right now. This ensures every dollar invested delivers immediate value, eliminating waste and strengthening our readiness for future crises.

To prepare for the next emergency, we need to practice now. That means running fast, focused clinical trials on today’s pressing questions—like the use of GLP-1s in non-obese patients—not just to generate insight, but to build the infrastructure and muscle memory for speed. FDA and HHS must work together to cut red tape, back these competitions, and redirect BARDA dollars away from stale legacy programs toward initiatives that actually make us faster. If Operation Warp Speed had finished even a few months faster, we could have saved hundreds of thousands of lives. Let’s not waste that lesson.

3.C. EQUAL TREATMENT FOR US AND FOREIGN MANUFACTURERS.

The FDA’s lower standards for foreign manufacturers are well documented. This, as you might expect, creates a perverse incentive for US businesses that wish to manufacture a good product affordably. They are disincentivized from doing it on our shores. As an example: US drug manufacturing facilities are subject to inspections with no advance warning; the FDA routinely gives up to 12 weeks advance notice to manufacturers in China. Predictably when the FDA gives such long advance notice to facilities they quickly clean up issues. Magically, inspections in China end up far cleaner. Perhaps it’s because Chinese firms destroy unfavorable records as Hengrui was caught doing?

At a minimum, the FDA’s office of regulatory affairs (in coordination with the appropriate center for each product) ought to enforce equal standards on foreign manufacturers that are no weaker than those enforced on US manufacturers, and hire more (or re-assign from other tasks) more foreign inspectors. This might be one of the few places where in contrast to DOGE efforts across the government a few more government employees would prove meaningful. Manufacturing regulations for US products should be universal, and if other nations are unwilling to adhere to ourstandards for our drugs, we should take the manufacturing away from them!

Conclusion

The sorts of reforms we lay out here would require an unusually bold administration - and a bold Congress to ensure the reforms are enduring throughout administrations. But they would save lives, perhaps millions of lives, with an abundance of medical interventions. And so far, this administration has had no problem being bold!

Competition and speed would flourish within the FDA and HHS, and the faster access and lower cost would embolden innovators outside of the government, drawing hundreds of billions of dollars more of risk-taking capital into the US biotech sector. Let’s tilt the playing field back towards investing and manufacturing therapies in the USA. Bold leadership can catapult the US back into the lead for biomedical and biological innovation - but it requires standing up to the internal bureaucracy who have “always done it this way”, and don’t want competition or major change: something that no FDA or HHS leader has managed to do in recent memory.

There are great minds and bold leaders willing to rethink how we do things who have come together to run the HHS, and in particular, the FDA. We are hopeful that the exciting leaders in this new administration will make major changes, and are eager to assist. Millions of lives, and the world’s greatest engine of biotech innovation, hangs in the balance!

In Free to Choose, Milton Friedman explains not only how to make FDA great, but also why we don’t need it at all.

Do we have what it takes to get rid of FDA?

Your first recommendation, i.e., eliminate GMPs for Phase 1 trial drugs, is based on a misunderstanding. In fact, FDA issued a final rule in July 2008 exempting Phase 1 drugs from the full GMP regulations and issued guidance that same month on what GMPs such drugs should follow. That guidance has about 8 pages of recommendations, and includes two sentences on stability:

"We recommend initiation of a stability study using representative samples of the phase 1

investigational drug to monitor the stability and quality of the phase 1 investigational drug during the clinical trial (i.e., date of manufacture through date of last administration)."

If a drug degrades significantly during the clinical study period it may cause direct harm and perhaps lead to a false conclusion about the drug's safety.

FDA rarely inspects clinical trial production and has always preferred a light regulatory touch at this stage of drug development. FDA reform is needed, but would prefer it be based on the truth and data.