Integrated Coverage Would Save Billions and Improve the Lives of the Least Well-Off

Why wouldn't we have it?

12 million Americans qualify for both Medicare and Medicaid coverage. These “dual eligibles” qualify for Medicaid because they are very poor and qualify for Medicare because they are either elderly or disabled.¹ Caring for this complex group of people is intrinsically challenging, but insurers and medical providers are also forced to grapple with a bifurcated reimbursement scheme which wastes money, fails to cover important medical services, and makes life difficult for some of the least well-off people in the country.

Blending Medicare and Medicaid funding into a single flow of money would powerfully align incentives for insurers and providers towards hiring caseworkers, nurses, and other professionals to pay much closer attention to the needs of dual eligible and engage in preventive care whenever possible. A future marketplace for dual eligible care will keep beneficiaries healthy and happy rather than allowing them to deteriorate into critical condition and then rushing them to the hospital — and would save enormous amounts of money in the process.

Insurers and risk-bearing providers that serve dual eligibles have shown that investing resources into caring for these vulnerable individuals up front reduces unnecessary hospitalizations and emergency room visits by huge percentages. A financial system that rewards providers for experimenting with new techniques for keeping patients healthy and avoiding pointless acute care will encourage entrepreneurs to continue constantly improve healthcare quality and allow the best ideas to go viral. We project that reform would keep healthcare simple for frustrated patients, make the dual eligible population substantially healthier, and save taxpayers 10s of billions of dollars annually.

The dual eligible population is one of the most costly, chronically ill populations in the country. 24% of dual eligibles need assistance with daily activities such as dressing and using the bathroom, 41% have a cognitive impairment, and 68% have three or more chronic conditions.² ³ ⁴ These individuals are disproportionately frail, minority, and female, with high prevalence of mental health, substance use, or housing instability challenges. At $34,000 per year, dual eligibles are much more expensive to insure than normal Medicare and Medicaid patients.⁵ The entire population costs taxpayers between $350B and $400B per year.⁶

These characteristics partly explain why dual eligibles cost 2–3x more than typical Medicare and Medicaid patients. But one of the main reasons why dual eligible care is so expensive is that financial responsibilities are split between federally-funded Medicare and state-funded Medicaid.⁷ This “bifurcated coverage” model creates unnecessary administrative complexity, encourages cost-shifting from Medicaid to Medicare, and makes it impossible for providers to effectively work together to care for those who need it most.⁸

Medicare, which primarily pays for acute-care services, was never intended to be a comprehensive benefit package. Dual eligibles have historically relied on Medicaid to provide ancillary services such as dental care, vision, and transportation, and most importantly to pay for long-term care services such as nursing homes, community-based care, and in-home services.⁹

This confusing financial division creates headaches for dual eligibles because any dual eligible beneficiary has to keep track of two enrollment periods, application deadlines, enrollment cards, and phone numbers, and may be enrolled in up to five different managed care plans!¹⁰ Living at or near the poverty line is challenging enough; dual eligibles shouldn’t have to deal with a Kafkaesque maze of healthcare bureaucracy as well.

Bifurcated coverage also wastes money in several ways. First, communication between Medicare and Medicaid often breaks down, which means that dual eligibles discharged from hospitals often can’t leave for multiple days because long-term care can’t be arranged efficiently. Second, providers are often confused over whether to bill Medicare or Medicaid, which creates administrative waste. Whether Medicaid or Medicare covers durable medical equipment (food, diapers, etc.) and home health expenditures varies depending on the severity of the patient’s condition, so it’s often very unclear who pays for what.

Third and most importantly, routine “cost-shifting” shunts dual eligibles from cheaper, more effective long-term care services — e.g. primary care physicians, routine check-ins by caseworkers, preventive medicine — into expensive acute care covered by Medicare once a patient’s health has spiraled out of control. ¹¹ Because neither Medicaid nor Medicare is incentivized to cover preventive measures, dual eligibles only infrequently receive vital diagnostics such as mammograms, and are often ineligible for home modifications such as grab bars which could prevent serious injuries. At least 39% of dual eligible hospitalizations are avoidable.¹² ¹³ ¹⁴ ¹⁵

A future marketplace for dual eligible care will keep beneficiaries healthy and happy rather than allowing them to deteriorate into critical condition and then rushing them to the hospital — and would save enormous amounts of money in the process.

Cost-shifting is often blatant and abusive. For example, after a 3-day hospital stay, Medicare covers Skilled Nursing Facilities (SNFs) for 100 days. After 100 days, dual eligibles in SNFs are covered by Medicaid at lower rates. According to experts we’ve spoken to, nursing facilities routinely game this system by waiting for the 100 days to expire and then pushing dual eligibles back into hospital care for at least 3 days so that they can reset the clock and force Medicare to sponsor another 100 days of SNF care at the maximum rate.

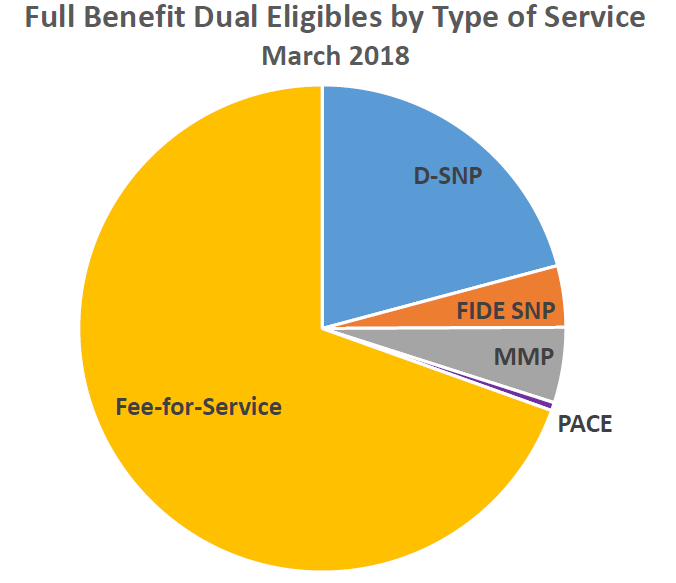

Experts have understood these problems for decades, and in the past 10 years the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) launched a variety of demonstrations in the states to experiment with integrated financing. A few of these programs (which go by a variety of silly acronyms) have been very successful, but even today, most of the dual eligible population is paid for by the traditional bifurcated coverage, fee-for-service model.¹⁶

The most successful kinds of demonstrations in the states are Financial Alignment Initiative “Medicare-Medicaid Plans” (MMPs) and a kind of Medicare Advantage plan called “Fully Integrated Dual Eligible Special Needs Plans” (FIDE-SNPs). On both models, Medicare and Medicaid consolidate payments to a single private insurer, which assumes complete responsibility for coordinating care for a given dual eligible patient. Government payments to the insurer are fixed or “capitated” at some predefined amount, and if the insurer keeps the patient healthy and saves money relative to the benchmark payment, they are rewarded for their thrift.

Both MMPs and FIDE-SNPs have shown real promise. In a 2018 study, the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPac) found that almost every mature MMP they interviewed had reduced the use of inpatient care and emergency room visits relative to traditional coverage for dual eligibles.¹⁷ Several independent studies confirm that MMPs and FIDE-SNPs can sponsor more innovative care models which are effective at driving down hospitalization rates and costs while keeping patients satisfied:

In Massachusetts, a study of 4,500 of Commonwealth Care Alliance MMP enrollees found they had 7.5% fewer hospital admissions and 6.4% fewer emergency department visits than in the 12 months prior to enrollment, and 82% of enrollees said they were satisfied with the program.¹⁸

In Arizona, a FIDE-SNP managed by Aetna called the “Mercy Care Plan” achieved a 43% lower rate of days spent in the hospital, 19% lower average length of stay, 9% reduction in emergency room visits, and a 21% lower readmission rate than fee-for-service Medicare for dual-eligibles.¹⁹

The Minnesota Senior Health Options program (MSHO), which is a FIDE-SNP for the elderly, has achieved 26% fewer hospital stays, 38% fewer emergency room visits, and made enrollees more likely to use primary care than elderly counterparts who received coverage from Medicaid, Medicare, or Medicare Advantage.²⁰

The more information that emerges on these “integrated coverage” models, the clearer it is that our country needs to move away from our fragmented financial scheme. We need to embrace a model that prevents cost-shifting, makes care-coordination the prerogative of a single institution, and aligns incentives for all parties towards providing better, cheaper care for every beneficiary. An improved financial model would draw on the lessons of the CMS demonstrations and selectively incorporate the best features of MMPs and FIDE-SNPs:

1) Three-Way Contracts

In an MMP, Medicare and Medicaid enter into a three-way contract with the insurer (the MMP) whereby the insurer receives a fixed payment in exchange for a set of specified healthcare services. Three-way contracts are an improvement over the FIDE-SNP approach, in which the insurer signs separate contracts with Medicare and Medicaid. Three-way contracts were widely preferred by every stakeholder interviewed in the MedPac study. Advance coordination clarifies financial responsibilities and avoids future disputes between Medicare and Medicaid.

Three-way contracts may involve a long, bureaucratized negotiation between a state and the federal government over which how much each party will contribute to payments for particular conditions, and to whom savings should accrue. Rather than negotiating each medical service, we propose that Medicare should cover whatever percentage of the ultimate fixed payment it has traditionally covered (e.g. 75%), with the state covering the remainder (e.g. 25%).²¹ Fixing financial responsibilities before deciding which services to cover would greatly simplify the planning process, saving time and money.

2) Competitive Bidding

Like all Medicare Advantage plans, FIDE-SNPs bid for contracts against benchmark reimbursement rates. By contrast, CMS and the states set rates for MMPs administratively. Competitive market bidding puts downward pressure on reimbursement rates and is superior to price control models where bureaucrats guess at the appropriate price for a basket of services without soliciting feedback from private players. Benchmark payments should be based on historical spending for a certain population size adjusted for demographic factors, and would evolve over time. One of our model’s main innovations is that it combines three-way contracts with a competitive bidding process.

3) Shared Savings

If insurers can cover their dual eligible population for less than the established benchmark price, they should be entitled to the majority of their savings (e.g. 50-75%). FIDE-SNPs typically allocate the rest of shared savings to Medicare and not to the states, whereas MMPs allow for states to share in savings. We prefer a hybrid model where the insurer, Medicaid, Medicare, and even the ultimate beneficiary all share in savings relative to the benchmark payment, and all share in losses if costs exceed the benchmark.²² This reward/penalty structure, which closely resembles that of the “Accountable Care Organizations” (ACOs) initiated as part of the Affordable Care Act, will stimulate healthcare entrepreneurs to devise new intervention strategies and regimens of care.

The state of Washington, which runs a “managed fee-for-service” dual eligible demonstration, achieved over $100M in savings over a 3.5 year period by awarding shared savings bonuses to “health homes” which manage complex dual eligible beneficiaries.²³ In the past several years, Colorado, Oregon, and Minnesota launched ACOs for their Medicaid populations, and we’re already seeing savings and great improvements in quality of care.²⁴ ²⁵ Two-sided incentives (rewards for success, penalties for losses) have proven to be more effective than reward-only models.²⁶ ²⁷

4) Full Benefits

Three-way contracts with insurers should require insurers to provide coverage of all relevant medical services. Today, MMPs provide coverage for behavioral health services, but some FIDE-SNPs do not. Since most dual eligibles have behavioral issues, this coverage should be universal. Coverage must include all traditional long-term and acute-care services and be flexible enough to pay for unconventional but cost-effective medical treatments such as providing meal plans or shelter to beneficiaries akin to Medicaid in-lieu of services. Where possible, administrators should set health standards and give insurers and providers freedom to experiment and identify cost-effective interventions.²⁸

5) Sticky Enrollment

A lesson from the demonstrations has been that many enrollees opt out between the enrollment date and the date when they start to receive services because they fear losing relationships with trusted providers, facing service restrictions, or are just uncertain about their new plans.²⁹ ³⁰ In fact, some of the most costly patients are opting out of the integrated care models while healthier patients remain in.³¹ As indicated above, those who remain in integrated coverage programs express high degrees of satisfaction and rarely disenroll. We need to educate dual eligibles on the benefits of integrated coverage, passively enroll beneficiaries, and consider allowing them to opt out only every few years.

If the normal dual eligible plan combined the best features of MMPs and FIDE-SNPs, private insurers, integrated delivery organizations, and providers would immediately step in to coordinate care. In the last few years we have been excited to see companies such as Cityblock Health and Landmark Health devise innovative strategies for managing expensive, vulnerable populations.

Cityblock and Landmark are deploying creative new methodologies such as permanently assigning caseworkers to each high-need Medicaid patient and scripting out meal plans for patients to prevent diabetes, high blood cholesterol, and other chronic conditions from spiraling out of control. We have been excited to see Landmark reduce avoidable utilization by 30–40% and achieve incredible rates of patient satisfaction in the process.³²

These and even more exciting innovations in preventive medicine will continue to save taxpayer dollars while keeping Americans healthy and satisfied — but only if our system of financial incentives stimulates new ideas and allows them to go viral.

Kenneth Thorpe has estimated that moving dual eligibles into coordinated care programs would save $10–20B a year because “well managed team based care results in lower rates of emergency room, clinic and hospital days.”³³ Based on the early results from MMP and FIDE-SNP programs as well as our diligence on private sector companies caring for expensive, complex populations, we think this figure could easily be $50B per year or more. We strongly encourage continued experimentation in the states but urge policymakers to apply the lessons of the demonstration programs by swiftly making an integrated coverage model for dual eligibles the default setting in America.