Don’t Just Donate. Innovate

Lessons in philanthropy

“You’re working because you want to change the world and make it better; if the company you work for is worthy of your time, why not your money as well?” — Larry Page [1]

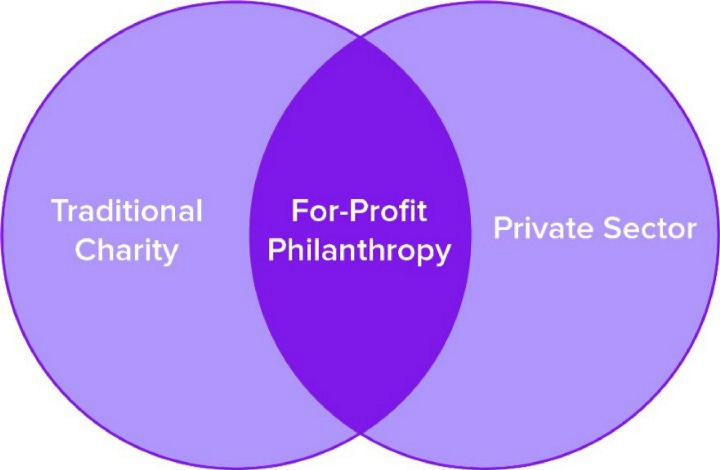

For most, the word “charity” evokes concepts of altruism and justice completely divorced from considerations of efficiency and profit. The distinction between the spheres of charity and commerce is reflected in the unique legal status accorded to each, and the kinds of people each sector tends to attract.

Today, this way of thinking is misleading and insidious. Our philosophy at 8VC is that many of the companies that present the greatest economic opportunities also create the greatest value for society. “For-profit philanthropy,” or altruistic investment guided by principles of accountability and return on investment (ROI), is often a compelling alternative to non-profit models.

Many of humanity’s most intractable challenges will only be solved through market-driven innovation. For-profit companies can attract top talent with the promise of equity, engendering a positive feedback loop: as talented people build and scale a business, they can leverage their expanding capital to hire more talented employees. Because the private sector has evolved processes and metrics for growth over many generations, for-profit models are more likely to efficiently accomplish their goals. Finally, viable business models easily attract capital and offer the best chance for systemic, durable solutions to social problems.

Wealthy donors typically fund 501c3 non-profits to address important social challenges. In the past year, Steve Ballmer and Michael Bloomberg have received attention for their civic charitable efforts — Ballmer recently launched USAFacts.com and the Ballmer Group, and Bloomberg’s What Works Cities initiative has done much to advise and improve America’s cities. I admire these men for their impressive acumen and good intentions. But Ballmer and Bloomberg are not taking full advantage of their experience and abilities. These icons of business are too quick to accept traditional non-profit models, and could use their skills to achieve greater social impact in these areas.

It’s true that certain causes require traditional charitable solutions, for instance disaster relief, and helping those in need who cannot help themselves.** Many “collective action,” “tragedy of the commons,” or “market failure” problems are best solved through government or non-profit action. But philanthropists consistently fail to grasp that there is a class of humanitarian projects where innovation is critical, and where solutions should be structured to create economic incentives. Instead of profit or social impact per se, donors should focus on “shared value” — creating economic value in a way that also addresses social needs and challenges.[2] Bishop and Green, who describe this paradigm as “philanthrocapitalism”, point out that “a profitable solution to a social problem…will attract far more capital, far faster, and thus achieve a far bigger impact, far sooner, than would a solution based entirely on giving money away.”[3]

My experiences building Palantir and running Addepar made me aware of serious problems with government, and inspired me to build a non-profit to look into state spending. Along with a team of several Stanford students, Zac Bookman and I created some of the first online transparency portals, and earned extensive press for our data and insights. We began receiving inbound interest from city officials and policymakers who wanted to compare and contrast their spending in similar ways, yet it was nearly impossible to do this with existing, decades-old systems. In fact, the officials we were working with barely understood their own data. We quickly realized that not only was this going to be an expensive problem for a non-profit, but that releasing studies and advising the leaders was unlikely to have a scalable impact. Only a for-profit corporation could attract the talent and capital necessary to build the technology solutions to power core government processes around budgeting, operational performance, and transparency. Only this kind of technological platform could scale to hundreds or thousands of governments at once.

We ultimately built a company called OpenGov, which fuses a for-profit model with a mission of making governments more effective and accountable. OpenGov powers governments across the country with a new “operating system” that enables agencies to make evidence-based decisions that drive better performance and improved outcomes for communities. It frees data currently trapped in complex legacy software and paper records, making the data available for streamlined budgeting, reporting, ad-hoc analysis, and citizen engagement in the cloud. OpenGov also networks customers together, providing them with the ability to understand key performance indicators compared to other similar government agencies.

We didn’t realize how many top city managers, CFOs, budgetary experts, and city councils would become excited about our innovation. Because OpenGov delivers a valuable public good as well as upside to stakeholders, it was possible for us to attract a bipartisan group of elite investors, advisors, and board members including John Chambers and Marc Andreessen.

The OpenGov team now numbers well over 100, and has created a big data platform and product setthat is used by more than 1,600 governments in North America. In 2015, OpenGov took the state of Ohio from 45th to 1st in the nation in a survey of transparency on government spending data. I have been thrilled to watch OpenGov continue to engage with government customers to determine how to innovate our product and boost sales — even as we deploy in city after city. OpenGov’s innovation promotes the public good, and its philanthropic impact has been far greater than that of a traditional charity. By helping local governments save money, we have improved the lives of citizens across the country while also advancing the interests of our shareholders.

Bloomberg’s What Works Cities initiative, which supplies cities with consultants and grants of millions of dollars to invest in data governance, is a truly necessary program, and is complementary to our work. Often, cities lack the resources or wherewithal to expand their data collection and analytics departments to create more effective policy. The technology that encodes best practices in government goes hand in hand with policy innovation encouraged by initiatives like this one. Unfortunately, most non-profit staff in general are instinctively skeptical of for-profits, reluctant to share their mission or align closely to build toward similar goals. Bloomberg, an entrepreneurial founder himself, should consider working directly with companies fixing the technology stack to improve city’s processes. His involvement in the details and his considered advice as a knowledgeable ally would accelerate adaption of new technology and make the core processes of perhaps the most important industry — government — more efficient.

OpenGov is just one example. Today we are witnessing a blurring of the boundaries between for-profit and non-profit initiatives. Eco-tourism and alternative energy production aim to achieve the twin goals of ROI and environmental sustainability. In education, income share agreements (ISAs) are making it possible for underprivileged kids to attend college, and some charter schools rely on for-profit models. Advances in Bio-IT have inaugurated a new age in medicine, and leading academics are encouraging their top students to build for-profit companies to harness their breakthroughs to cure diseases and save lives.

Here in Silicon Valley, Google.org — the for-profit charitable arm of Google Inc. — has made enormous strides as a philanthropy, leveraging data to improve educational opportunity, fight racial injustice, and develop remittance infrastructure for the world’s poorest people. And as the pull quote indicates, Larry Page recently intimated that he would prefer to fund one of Elon Musk’s for-profit companies than donate to a traditional charity, because he believes corporations such as SpaceX and Tesla are some of the most powerful engines for social progress.[4]

In general, for-profit philanthropy may be an important complement to a traditional 501c3 for several reasons:

For-profit philanthropies can raise more money from prospective investors because they offer a return on investment. This makes it easier to grow and scale an organization and increase the overall capacity of the giving sector.

For-profit companies focus on results and substance; non-profit employees often lack clear objectives or KPIs, leading to slower progress and lower efficiency. This structural problem can stall non-profit efforts relative to performance driven cultures.

“Market discipline” holds for-profit charities accountable for wasteful spending. Customer relationships generate direct feedback, and the boards, management, and technologists at for-profit companies are investors with “skin in the game”. Empirically, equity, and metrics-driven, for-profit cultures encourage employees to work harder, iterate faster and deliver innovation.

For-profit philanthropies are more responsive to new developments and shifts in demand than relatively slower moving non-profit charities. They can help cover gaps in the market more swiftly than their traditional counterparts.

For-profit companies are typically better able to attract people with proven track records of success in growing enterprises, and to maintain execution-driven cultures over long periods of time. This sustained, positive-feedback loop is necessary to scale and maximize the effect of a philanthropic endeavor, and will deliver exponential results.

Non-profit organizations are reliant on recurring donations, which makes it difficult to engage in long-term planning, and completely subjects non-profits to the direction of their (usually opinionated) board members. Whereas for-profit companies can build recurring revenue to ensure their survival, tackle problems with longer time horizons, and operate with relative autonomy; non-profits must focus on capital preservation and pleasing their donors.

For-profit philanthropy won’t solve every social and humanitarian problem, but it is often superior to a 501c3 approach. Donors such as Michael Bloomberg became wealthy by bringing together top talent in for-profit, mission-driven cultures that figured out how to build and deliver technologies which transform core processes in large industries. Entrepreneurs build successful enterprises in the face of scarcity, and they should consider carrying this mindset with them as they pivot to charitable endeavors. If billionaire donors had more time and energy, but less money to address these important missions, they might be more likely to consider the ROI of helping to build for-profit companies which can both attract talent and achieve sustainable social impact in the spaces they care about. I encourage more great entrepreneurs and investors to consider partnering with mission-driven businesses as part of their philanthropic efforts, so we can ally, learn, and benefit from what they create.

* (From Above) We truly believe in many traditional non-profits in addition to innovative, mission-driven businesses. For instance, we strongly support Ashton Kutcher’s Thorn, which works with tech innovators to stop child-trafficking and to help law enforcement find and rescue abused children. Arthur Brooks is doing incredible work at AEI to encourage free enterprise policy that lifts the bottom of society and restores dignity to America’s least well off. The International Justice Mission has done much to alleviate desperate poverty in the Philippines. Leaders we admire such as Bill and Melinda Gates, Michael Bloomberg, Laurene Jobs and others have done much to save lives around the world, positively influence education and immigration policy, support the natural environment, and contribute to other important social missions. The list goes on. There are hundreds or perhaps thousands of other worthwhile non-profits that deserve charitable donations, and our intent is to complement these efforts in some cases with mission-driven, for-profit cultures, but not to replace them.

[1] Yarrow, Jay. “Larry Page: I Would Rather Give My Billions To Elon Musk Than Charity.” Business Insider, Mar. 20, 2014. http://www.businessinsider.com/larry-page-elon-musk-2014-3

[2] Porter, Michael and Mark Kramer. “Creating Shared Value.” Harvard Business Review, January-February 2011.

[3] Bishop, Matthew and Michael Green. “Philanthrocapitalism.” Bloomsbury Press, 2008.

[4] http://www.businessinsider.com/larry-page-elon-musk-2014-3