Brave Days, Great Days

What will we be remembered for?

Then out spake brave Horatius, The Captain of the gate: 'To every man upon this earth Death cometh soon or late. And how can man die better Than facing fearful odds, For the ashes of his fathers And the temples of his Gods' - Horatius, by Thomas Babington Macaulay

In the nascent days of the Roman Republic, the city was invaded by the Etruscan king Lars Porsena, on behalf of Sextus Tarquinius, the son of Rome’s final (and deposed) king. A group of Romans stood against the Etruscans at the Pons Sublicius, the first bridge spanning the Tiber River in the city. On the Western side of the Tiber was the hill Janiculum, outside historic Rome; on the other was the Aventine Hill, at the city’s heart. With the Etruscans amassing on the Western side, the only way to defend Rome was to keep the wooden bridge long enough to hack it apart. In Macaulay’s retelling of the ancient story, the hero Publius Horatius Cocles told his countrymen:

‘Hew down the bridge, Sir Consul, With all the speed ye may; I, with two more to help me, Will hold the foe in play. In yon straight path a thousand May well be stopped by three. Now who will stand on either hand, And keep the bridge with me?’

Two men answered the call: Spurius Lartius and Herminius. And the “dauntless three,” as Macaulay calls them, defended the bridge until its destruction. Horatius jumped from the collapsing bridge into the Tiber. In some tellings, that was his end; in others, he swam back to Rome. Either way, he became a hero, memorialized throughout the centuries of flourishing under the Republic and Empire. Macaulay recounts:

And still his name sounds stirring Unto the men of Rome, As the trumpet-blast that cries to them To charge the Volscian home; And wives still pray to Juno For boys with hearts as bold As his who kept the bridge so well In the brave days of old.

Macaulay’s ballad was part of his 1842 collection, The Lays of Ancient Rome. It is a particularly 19th-century-British publication: interested in heroism, its sources, and its remembrance. Macaulay was a senior military and financial official, as well as an historian — with a keen sense of the value he saw in the British civilization, which he fought for.

As a boy at the Harrow School, Winston Churchill won a prize for reciting all 1200 lines in Horatius [1]. Speaking at the school decades later in October 1941 after his country had weathered the Blitz, the Prime Minister instructed the boys with an echo of Macaulay:

“Do not let us speak of darker days: let us speak rather of sterner days. These are not dark days; these are great days — the greatest days our country has ever lived; and we must all thank God that we have been allowed, each of us according to our stations, to play a part in making these days memorable in the history of our race.”

For Macaulay, the defense of Rome made for “brave days” and for Churchill, the defense of Britain made for “great days.” Churchill says “memorable,” too, well aware that the story of Horatius had survived for 2,500 years in one form or another. Churchill was inspired to be such a defender, and the British fascination with heroes and ballads played a part in that, however small. Today, that country is quite different; the Lays aren’t often taught. Modern man has become wary of heroes — and of unabashed celebrations of virtue. Because what if the heroes were… controversial? [2]

The truth is that anyone who fights for something real will inevitably be seen as controversial. Churchill knew that what had been built by his forefathers — Britain itself — was worth fighting for. He didn’t think there was any option except to fight, “to go on to the end” as he famously said after the Dunkirk evacuation. Do his inheritors think the same? The sight in 2020 of a large gray box around a statue of Churchill in London, the city he saved from Nazi annihilation, doesn’t inspire confidence. The men who grew up on Macaulay and believed in heroism, would never have tolerated such an outrage.

Like Churchill, Horatius thought that the young republic being built on one side of the Sublician bridge was worth defending from the army on the other side. A thousand years later, that conviction died, and imperial Rome was sacked thrice in a single century. As the story goes, eventually it was Romans who opened the gates for the Vandals. Those who built Rome fought for Rome. Those who didn’t build it didn’t fight for it.

Unlike Churchill and Horatius, we don’t face an army threatening our country in the United States. But we do face a war on our values, waged both from within and outside of the United States. One big question for us is, will American builders fight for America? Unfortunately, it’s taken too many entrepreneurs too long to notice that we’re in a conflict at all. For many American liberals — I mean that in the original sense of the word — and especially American Jews, the October 7th attack and its aftermath was a jolt-awake moment.

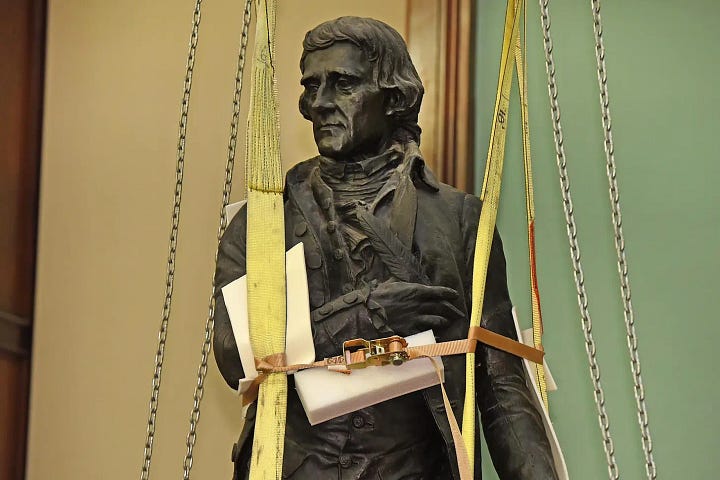

If this is you, you’re late to the party, but I welcome you anyway. And now that you’re here, it’s time to hear what you’ve been missing, which is that bad cultural ideas have been tearing Western societies apart for much longer than the last seven months. It turns out that the ideas that lead students to praise terrorist attacks are the same ones that justify vandalizing statues of Churchill (or in America, Jefferson!). Those same ideas justify ending meritocracy, crushing upward mobility for millions in the name of “equity.” It’s those same ideas that have taken over institutions that the whole public relies on to be neutral, or at least functional: schools, hospitals, medical associations, government agencies, NGOs, you name it. Today, we’re reaping the consequences of allowing such takeovers.

Now you’re here. Something is wrong. Dangerous times are ahead if people don’t find a voice. Institutions are not self-correcting without a fight. And yet, it doesn’t require that many courageous people to make a difference. (Remember Horatius: “...a thousand May well be stopped by three. Now who will stand on either hand, And keep the bridge with me?”)

We have to Build and Fight. Building — enterprise, the creation of new things — is itself a rebellion against decay. It is absolutely essential to a free society, and to the United States. But building businesses, even bold businesses, isn’t enough. And too often, builders are not focused enough on fighting for the values that make enterprise possible in the first place! President Milei puts this point well:

“Milton Friedman used to say that 'the social role of the entrepreneur is to make money.' But that is not enough. Part of their investment must include investing in those who defend the ideals of freedom, so the socialists can make no further advances. And if they don't do it, they [socialists] will get into the state and use the state to impose a long term agenda that will destroy everything it touches. So we need a commitment from all those who create wealth to fight against socialism, to fight against statism, and to understand that if they fail to do so, the socialists will keep coming… We cannot take a day off, because when we rest, socialism creeps in.”

Building without fighting cedes the field to those who fight without building. Unfortunately, this is a widespread problem among what we could call the moderate business elite in the United States — wealthy people that don’t bother fighting against the immense pressures to shut up and go along. The excuses are endless. Many of these people see the armies on the other side of the river. They have the right values but don’t voice them. It will attract negative press. They tell themselves stories that what they think or do doesn't matter, because they don't believe in heroes. After all, those who talk about things like “the defense of civilization” sound a bit loony! What could really go wrong with $50 trillion in debt, or ideological extremists in charge of what information is available to the public?

The concept of F-U money is often talked about with wealthy people. But who is really spending that F-U money? Fewer than you’d hope — because those who are well off feel they have more to lose by being seen as controversial, or cast out of elite social circles. Do you remember what happened to my friend Peter Thiel after he spoke at the Republican National Convention in 2016 on behalf of Donald Trump? Or more recently, when Elon Musk bought Twitter? They were warnings: don’t go out of bounds. When Peter and Elon fought back, those were two real instances of F-U money.

But suppose you don’t want to get involved in heated presidential races, or buy a social media company. How do you start to fight? It starts with using your possessions appropriately. What are your possessions?

Your Time

Your Money

Your Voice

Your Name

Not everyone has large sums of money or a well-known name. But for those that do, your obligation is to use it to fight, not abet, brokenness. Do not give your money to institutions that have lost their way, that are husks. Do not lend your name to dysfunction; the titles and “honors” are actually markers of dishonor if you aren’t fixing things. What you spend your time on matters; your most productive years are not trivial. Your frameworks for how to build new things don’t get better in old age; building philanthropies and institutions now is better. If you don’t know where to start, find a bold partner, someone who shares your values and is building already.

Build new institutions — a university, a bold company to fix broken processes, an organization to fight for better government policy. And don’t stop then. Fight! Speak the truth. Because if you’re starting anything worthwhile, it won’t be smooth sailing into port. You will meet resistance. You will be attacked. To a cynic, it might sound obnoxious, or corny. But it’s true: a society that rejects the idea of heroism will produce fewer and fewer heroes, and at the same time turn into the type of place that needs them. Whether and how we fought back when we realized we were at war is what we’ll be remembered for (or why we won’t be).

Today, too many people have internalized the idea that being labeled as “controversial” by journalists or politicians isn’t worth being bold — and that joining the fight will actually result in more division. Again, this is a self-fulfilling prophecy; when we lack bold, principled, competent fighters, there are fewer people to unite us. Macaulay notes how heroism and the defense of shared values actually united Romans:

Then none was for a party;

Then all were for the state;

Then the great man helped the poor,

And the poor man loved the great:

Then lands were fairly portioned;

Then spoils were fairly sold:

The Romans were like brothers

In the brave days of old.If you believe that this civilization matters, then you’ll find a way to fight for it. And someday, perhaps on another planet or in another language, someone will end up reading a ballad about you — about your brave, great days of old.

[1] Horatius - full 1200 line ballad

[2] Two reimagined ballads by ChatGPT:

“Horatius, the Controversial” In the city of Rome, so ancient and bold, A tale of valor, or so we're told, Horatius, a name engraved in stone, But can heroes like him truly atone? Against the Etruscans, he took his stand, Defending the city, sword in hand, But in this age of doubt and strife, Can we truly celebrate his life? For in the shadows of his glorious feat, Lurks the questions we dare not greet, Was it bravery or blind obsession, That drove him to defend without question? In a world where heroes often fall, Their virtues tarnished, their flaws call, Horatius stands in history's light, But can we reconcile wrongs with right? Amidst the cheers and victory's song, A sense of unease lingers long, For heroes of old, with their valor bold, Are they truly worthy of tales retold? “Horatius, Wary of Controversy” In Rome, where legends rise and fall, There lived a man known to all, Horatius Cocles, his name proclaimed, But his deeds, in controversy, remained. For when the Etruscans threatened Rome's gate, Horatius stood in a conflicted state, Afraid to embrace the hero's role, For fear of controversy taking its toll. Then Horatius, with a weary sigh, Looked upon Rome with a troubled eye: "Why cling to walls that crumble with time, When controversy stains every line? As the Etruscans advanced, their army vast, Horatius felt his resolve surpassed, The weight of controversy too much to bear, He chose to surrender, in deep despair. Rome fell to the invaders' might, As Horatius watched, torn by plight, For fear of controversy, he let it fall, And Rome's proud walls crumbled, to the invaders' call.

Brilliant essay, Joe. A moving call to arms. I’ve always loved Macaulay, and I knew Churchill did too—but I had no idea he’d memorized the entire poem!

Outstanding article Joe!